MVVM Architecture in SwiftUI: From ObservableObject to @Observable - Part 3

The Evolution of State Management in Declarative UI: Migrating from ObservableObject to the Swift Observation Framework

The move from the Combine‑based ObservableObject protocol to Swift’s native Observation framework is a fundamental shift for SwiftUI. For years, state updates were driven by a push‑based invalidation model where objects broadcast generic change signals that trigger broad view re‑evaluations. This worked for small apps but struggled at scale, especially with large lists, nested reference models, and complex data dependencies. With the @Observable macro in Swift 5.9, the model becomes pull‑based and access tracked, giving precise invalidation, cleaner architecture, and better performance by default.

Historical Context: Limits of the Combine Era

The ObservableObject protocol relied on Combine’s publishers, especially the synthesized objectWillChange stream from @Published properties. When a published property is mutated, the object sends a change event before the actual value update, notifying subscribers that it is about to enter a dirty state. See Apple Developer: Migrating from ObservableObject to Observable.

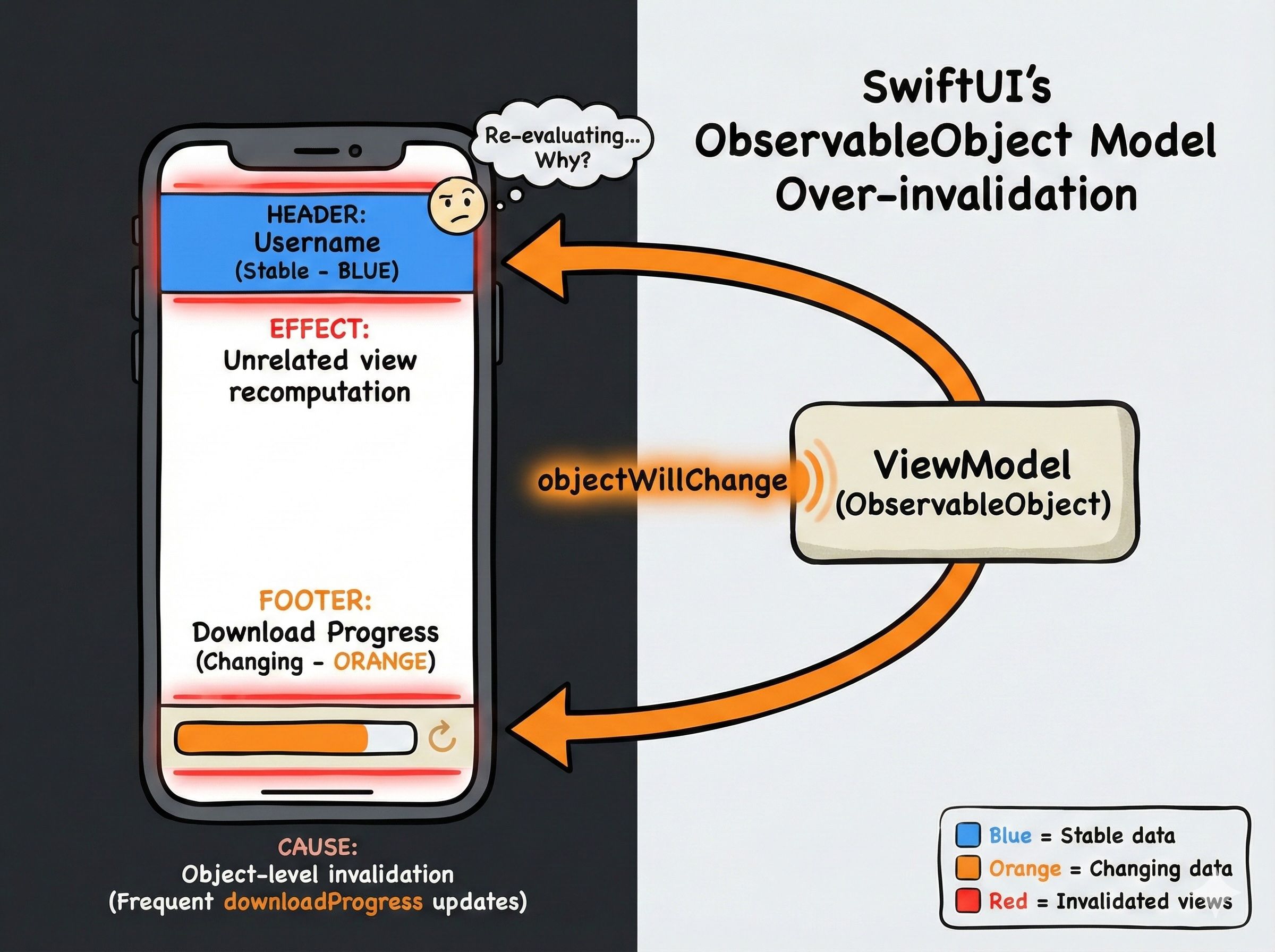

In practice, a view subscribing to an observable instance—whether via @ObservedObject, @StateObject, or @EnvironmentObject—depends on the entire object rather than specific properties. Consider a profile view where the header displays a username and the footer shows a high‑frequency downloadProgress. Each progress tick invalidates the entire view hierarchy, forcing unrelated areas like the header to re‑evaluate. See SwiftLee: Performance increase with @Observable.

This over‑invalidation led teams to fragment view models into smaller units to isolate updates, often at odds with domain‑driven design. A common structural flaw involved nested observable objects: a parent view model referencing a child ObservableObject would not automatically forward the child’s changes to the parent’s objectWillChange. Changes in the child were invisible to views bound to the parent unless developers wrote manual forwarding code.

Legacy Workaround for Nested Objects

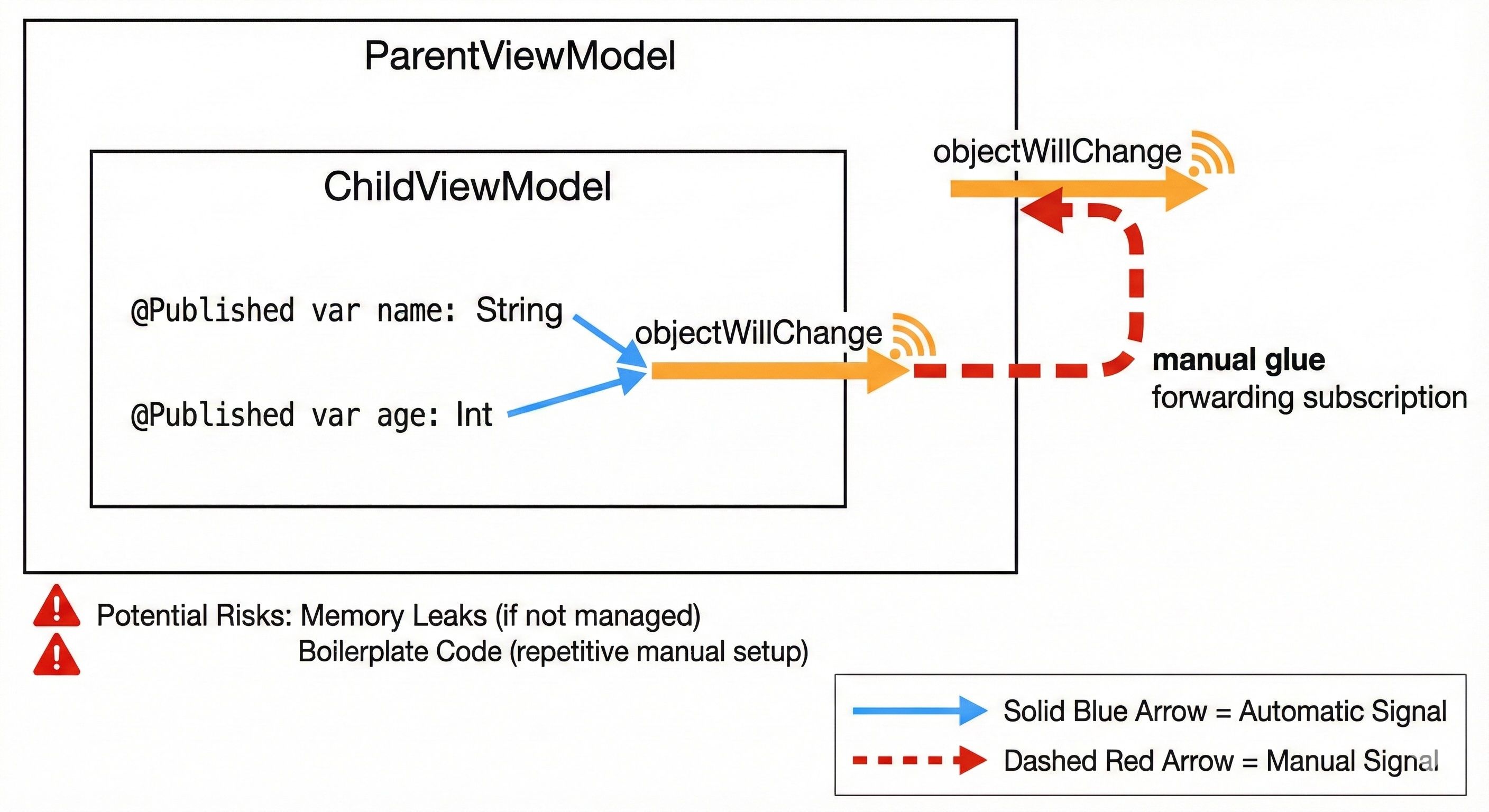

When a parent holds a child ObservableObject, the parent does not automatically forward changes from the child. Developers implemented glue code by subscribing to the child’s objectWillChange and piping it to the parent’s publisher. See Swift Forums: Observing nested ObservableObject.

// Manual forwarding of nested changes

class ParentViewModel: ObservableObject {

@Published var child: ChildViewModel

var cancellables = Set<AnyCancellable>()

init(child: ChildViewModel) {

self.child = child

child.objectWillChange

.sink { [weak self] _ in

self?.objectWillChange.send()

}

.store(in: &cancellables)

}

}

This code adds complexity and can introduce leaks if cancellables are mismanaged. It also dilutes the idea of a single source of truth because synchronization becomes manual and error‑prone. See Stack Overflow: Bind to nested ObservableObjects.

Mechanics of Observation: A Deep Dive

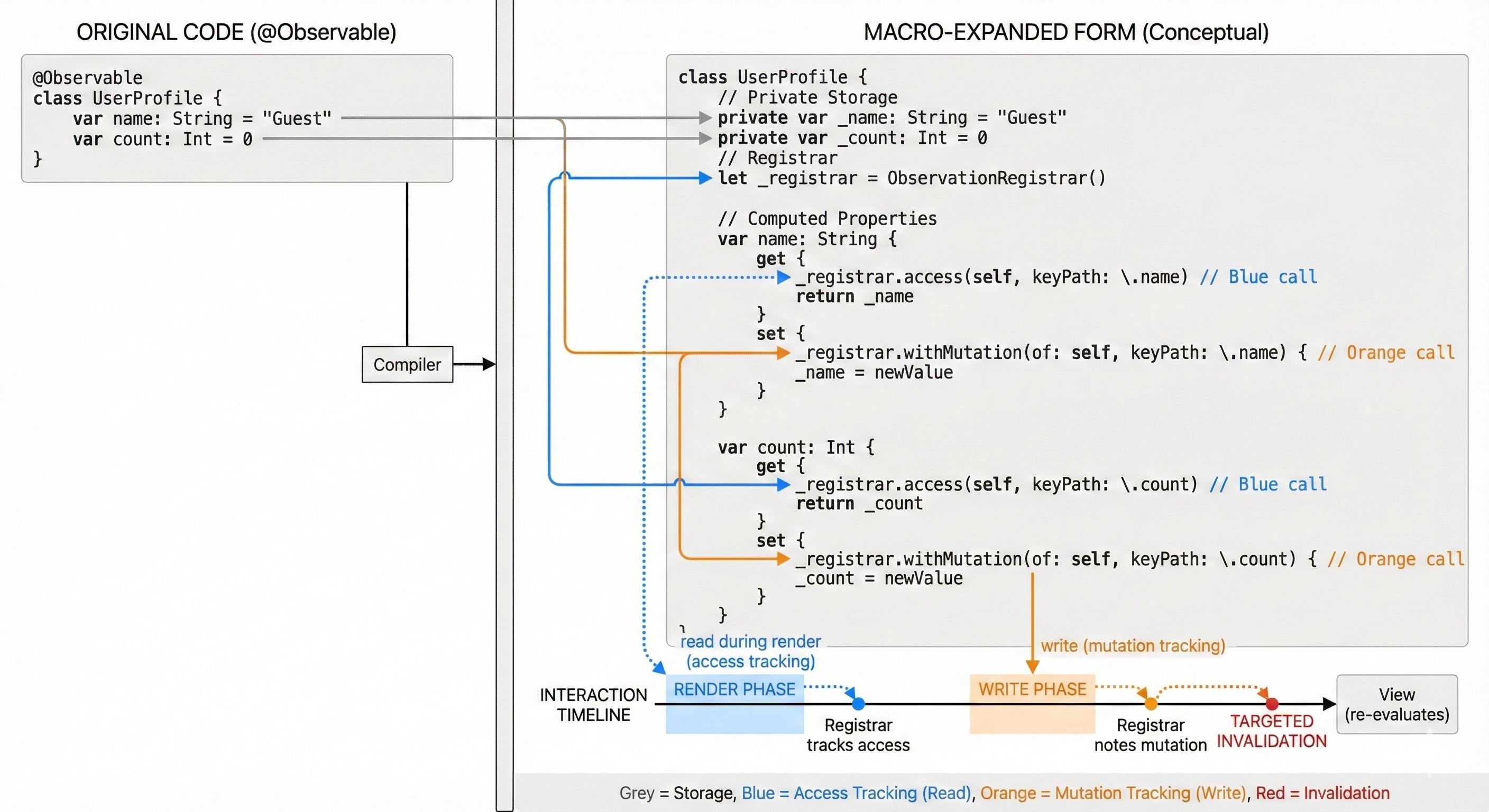

The Observation framework abandons Combine publishers and uses compiler‑generated access tracking. The @Observable macro expands a class into an observable type with a private storage backing and computed properties that intercept reads and writes through an ObservationRegistrar.

@Observable class UserViewModel {

var name: String = "Guest"

}

// Conceptual expansion (simplified)

class UserViewModel: Observable {

@ObservationIgnored private let _$observationRegistrar = ObservationRegistrar()

@ObservationIgnored private var _name: String = "Guest"

var name: String {

get {

_$observationRegistrar.access(self, keyPath: \.name)

return _name

}

set {

_$observationRegistrar.withMutation(of: self, keyPath: \.name) {

_name = newValue

}

}

}

}

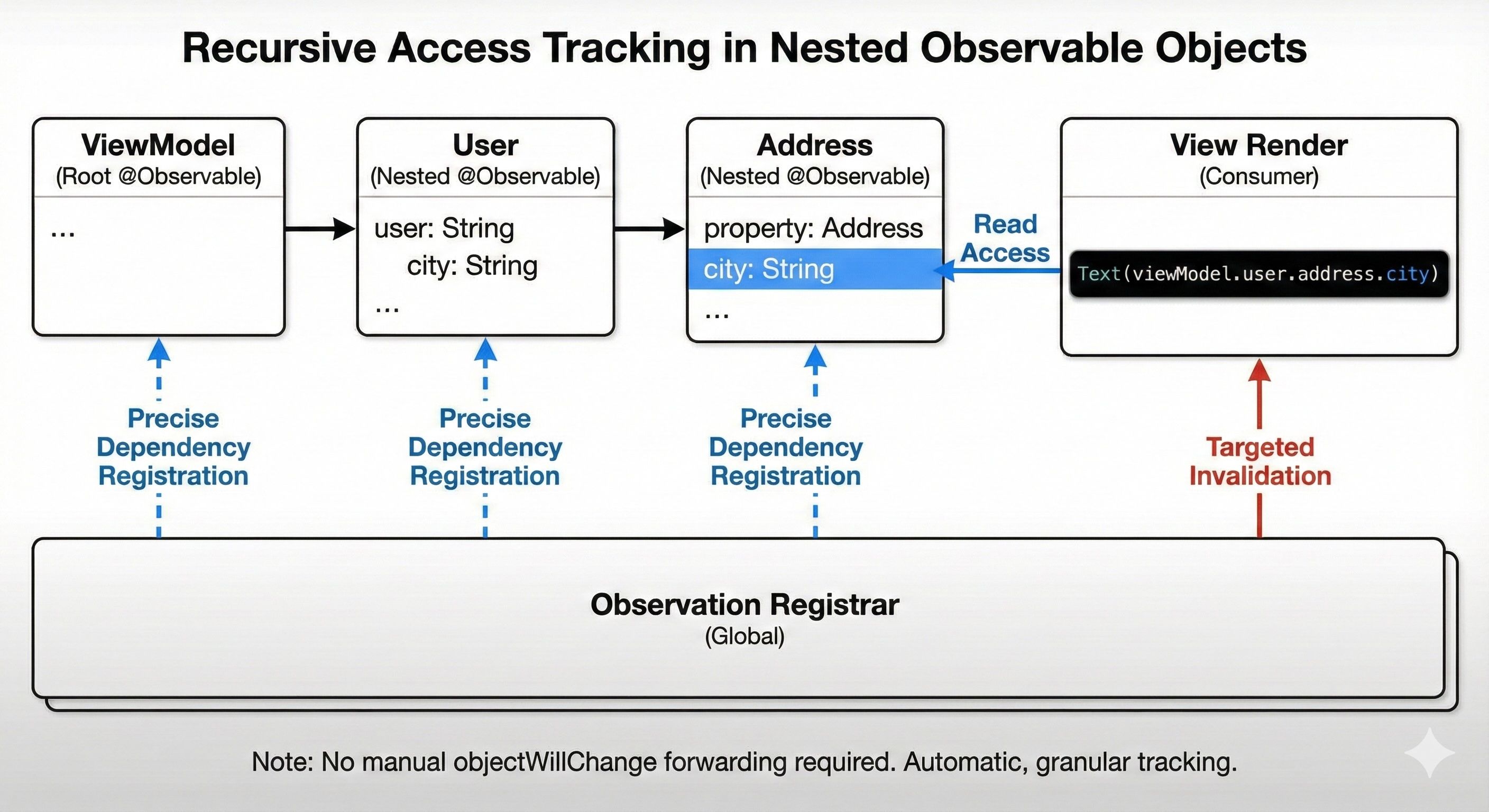

During a render, SwiftUI installs a tracking scope. When a view reads viewModel.name, the getter records the dependency. When name changes, the registrar invalidates exactly the views that read that key path, and nothing else. This is the core of granular invalidation and explains the performance wins on lists and complex hierarchies.

To opt out of observation for internal or non‑UI fields, use @ObservationIgnored. This keeps the registrar from tracking churn on values that never drive UI. See Donny Wals: Observable in SwiftUI.

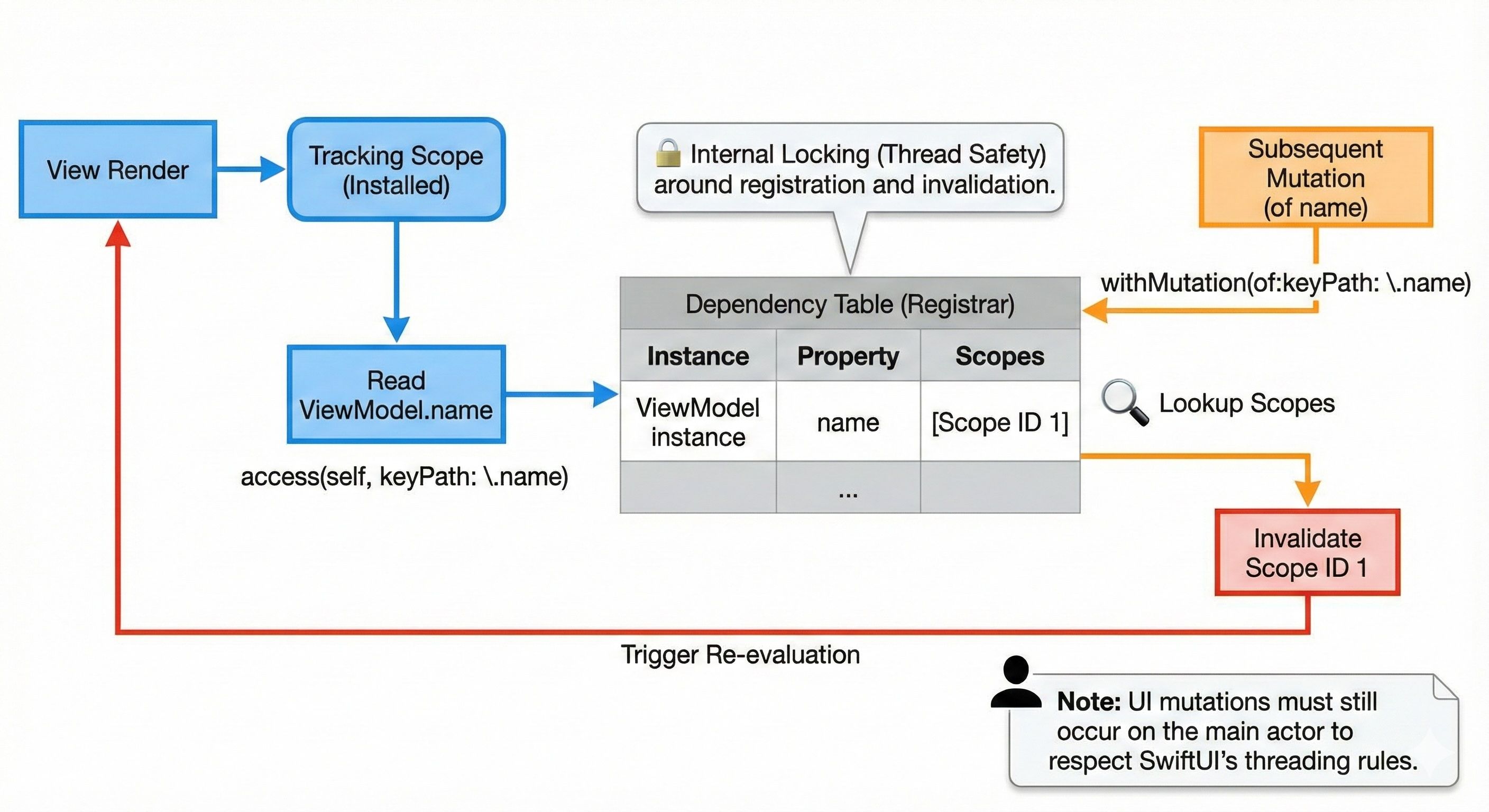

ObservationRegistrar: The Engine of State

The ObservationRegistrar is the thread‑safe core that manages access tracking and invalidation. During the access phase, when a view evaluates its body, a tracking scope is installed. Each property read calls access(self, keyPath:) and the registrar records a precise dependency between the active scope and the specific key path of the specific instance being read. During mutation, setters call withMutation(of:keyPath:). The registrar looks up the exact scopes registered for that key path and triggers their invalidation closures. Views that did not read that property are not notified and do not re‑evaluate. This selective behavior is the foundation for property‑level granularity and improved performance. See Apple Docs: ObservationRegistrar.

Thread safety is provided by internal locking around registration and invalidation so concurrent reads and writes remain consistent. UI mutations must still occur on the main actor to respect SwiftUI’s threading rules. When views leave the hierarchy, SwiftUI tears down their scopes and the registrar drops the associated dependencies, keeping memory safe in normal usage. For manual scopes created with withObservationTracking, ensure the scope is released or a subsequent mutation occurs to allow the change closure to fire and the dependency to be cleaned up. See community analysis such as Jano.dev: Observation Framework.

Structural Migration in MVVM

Moving from ObservableObject to @Observable changes how view models are owned, passed, and injected. The taxonomy of wrappers simplifies significantly. The old @StateObject becomes @State for ownership and lifecycle. The old @ObservedObject becomes a plain property for dependency. The old @EnvironmentObject becomes @Environment for injection. @Published is no longer needed because stored properties of @Observable types are tracked by default.

Each mapping carries a clear role. @State owns the instance and manages its lifecycle within the view. A plain reference (let or var) expresses a dependency that is created elsewhere and passed in, and reading properties in the body establishes observation implicitly. @Environment retrieves shared instances from the environment hierarchy. Removal of @Published reduces boilerplate because observation is opt‑out rather than opt‑in.

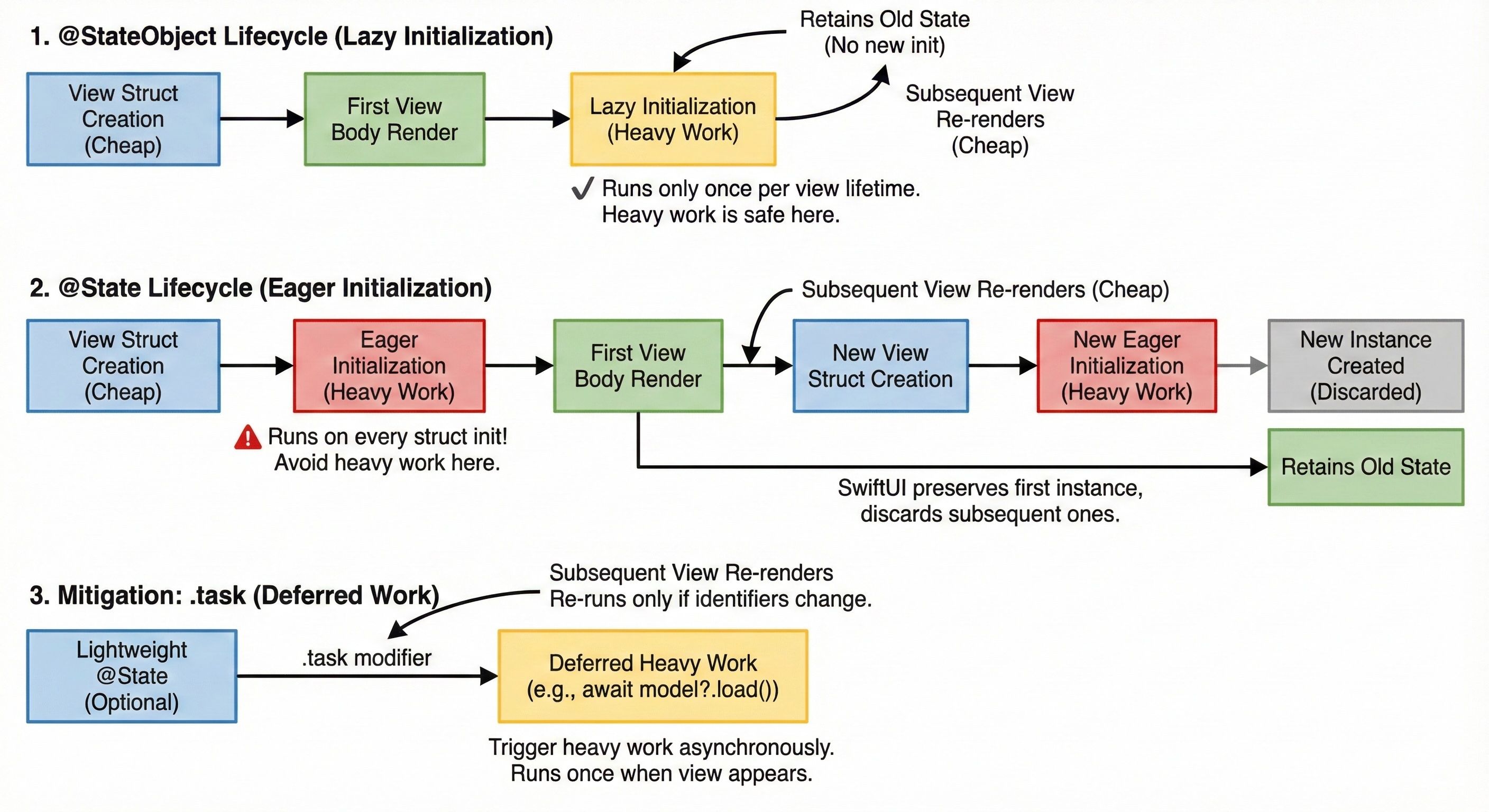

A dangerous change involves the swap from @StateObject to @State. @StateObject initialized lazily and only once per view lifecycle, while @State initializes eagerly when the struct initializes. If an initializer performs heavy work, that work might run more often than expected, even if the state instance is ultimately preserved by SwiftUI. See Jesse Squires: Observable macro is not drop‑in and Swift Forums: init called multiple times with @State.

Mitigation is straightforward. Keep initializers light and move heavy setup into methods triggered by .task or .onAppear. When appropriate, initialize optional state and populate it lazily inside a task. This keeps startup fast and avoids repeated heavy work.

// Lightweight state ownership and deferred work

@State private var model: MyModel?

var body: some View {

Group {

// ... UI ...

}

.task {

if model == nil { model = MyModel() }

await model?.load()

}

}

Passing observable models implicitly establishes observation. Any property read inside body or helpers called by body creates a subscription. For read–write access in child views, wrap the model in @Bindable to project bindings. A view that owns state via @State gets bindings automatically with the dollar prefix; a view that receives a model must create a bindable proxy.

struct EditView: View {

@Bindable var model: UserViewModel

var body: some View {

Form {

TextField("Name", text: $model.name)

Toggle("Active", isOn: $model.isActive)

}

}

}

Nested Object Revolution

The nested object problem disappears with @Observable. If a view reads viewModel.user.address.city, and Address is observable, the dependency is registered on that exact property of that exact instance. There is no need to wire objectWillChange manually, and domain‑driven modeling becomes natural again. See Holy Swift: Solving nested observables.

@Observable class Inner { var val = 0 }

@Observable class Outer { var inner = Inner() }

// Reading outer.inner.val triggers updates exactly where needed.

Performance Internals

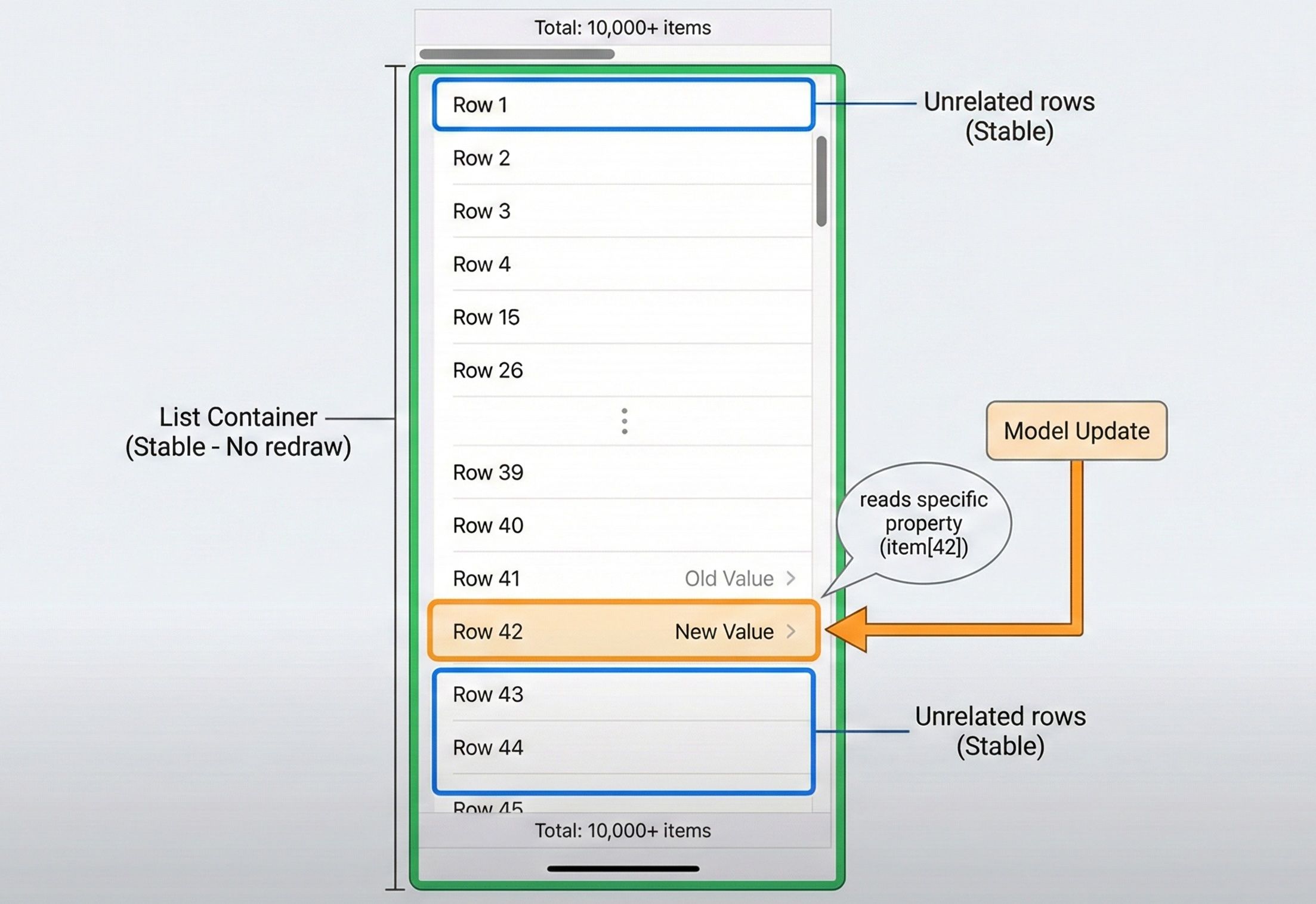

Granularity transforms invalidation costs. In the legacy model, the cost of updates grows with the number of views observing an object multiplied by the frequency of any property change on that object. In the modern model, the cost grows with the number of views that read a specific property multiplied by the frequency of that property’s change. This is why unrelated views stop recomputing and lists scale dramatically. See SwiftLee: Performance increase with @Observable.

Large collections benefit greatly. A list of tens of thousands of items can update a single row without disturbing the others. When item #42 changes, only the view that read item[42] invalidates; the parent that reads the array reference does not rerender because the reference and count are unchanged. See Medium: Deep understanding of SwiftUI List.

Subtle memory risks remain. Complex derived properties may introduce strong reference cycles if they capture self in closures. Observation itself is thread‑safe via internal locking, but UI mutations must still occur on the main actor. Lifecycle teardown of views cleans tracking scopes automatically.

Bridging the Reactive Gap

The loss of automatic $ publishers breaks Combine‑based side effects like debouncing and throttling. In @Observable types, the $ syntax inside views projects a binding rather than a publisher, so operators like debounce and sink cannot be used directly. Prefer Swift Concurrency with .task(id:) in views for debounce and cancellation semantics.

struct SearchView: View {

@State private var viewModel = SearchViewModel()

// Debounce search queries for 0.5 seconds

var body: some View {

TextField("Search", text: $viewModel.query)

.task(id: viewModel.query) {

try? await Task.sleep(for: .seconds(0.5))

await viewModel.performSearch()

}

}

}

When logic must live inside view models, use an actor‑backed debouncer to serialize work safely.

actor SearchDebouncer {

private var currentTask: Task<Void, Error>?

// Submit a search query, debouncing previous submissions.

func submit(query: String, action: @escaping (String) async -> Void) {

currentTask?.cancel()

currentTask = Task {

// Throw error if the task is canceled before the delay.

try await Task.sleep(for: .seconds(0.5))

await action(query)

}

}

}

For complex pipelines that depend on Combine operators such as combineLatest, flatMap, or merge, expose manual publishers from observable models while keeping UI observation on @Observable.

See guidance and discussion in Donny Wals: Observable in SwiftUI, Swift Forums: observing outside View, and Stack Overflow: publisher from @Observable values.

@Observable class HybridViewModel {

var query: String = "" {

didSet { querySubject.send(query) }

}

@ObservationIgnored

private let querySubject = PassthroughSubject<String, Never>()

var queryPublisher: AnyPublisher<String, Never> {

querySubject.eraseToAnyPublisher()

}

}

For the above code examples, the .task(id:) modifier installs a task that cancels and restarts whenever the identifier changes, which matches debounce behavior. A sleep creates the delay window and cancellation drops in‑flight work. Actor‑based debouncers bring these guarantees into models without relying on view lifecycle. The hybrid approach connects didSet changes to a subject so Combine pipelines can operate while views still benefit from precise observation.

Testing Strategies

Testing direct mutations is unchanged: set a property and assert the new value. To test that observation actually triggers, use withObservationTracking and expectations. Remember the nuance: the change handler runs with will‑set semantics—before the new value is stored—so read the new value after the mutation or inside an asynchronous continuation.

withObservationTracking {

_ = vm.name

} onChange: {

expectation.fulfill()

}

vm.name = "Updated"

Backward Compatibility

Teams supporting iOS 15 or 16 can adopt the model today using Point‑Free’s Perception library. Replace @Observable with @Perceptible and wrap bodies with WithPerceptionTracking. When support for older OS versions is dropped, perform a straightforward rename back to the native macros. See Point‑Free: Perception.

Conclusion

Migrating to @Observable removes imperative glue, enables natural nested modeling, and converts broad invalidation into precise property‑level updates. Syntax becomes cleaner, and concurrency replaces reactive operators for side effects. The result is a system that is performant by default, simple to reason about, and robust at scale. For teams on older platforms, backports make it possible to adopt the architecture immediately and migrate later with minimal effort.

References

Apple Developer: Migrating from ObservableObject to Observable. SwiftLee: Performance increase with @Observable. Stack Overflow: Bind to nested ObservableObjects. Swift Forums: Nested ObservableObject observation. Apple Docs: ObservationRegistrar. Jesse Squires: Observable macro is not drop‑in. Point‑Free: Perception.